The 2024/2025 Namibian drilling campaign has revealed a more complex geological picture than anticipated. While multiple wells have confirmed hydrocarbons, technical challenges around reservoir quality and gas management have emerged as key hurdles for commercial development. However, these challenges, when viewed in the context of other frontier basin developments, aren't necessarily insurmountable.

Recent drilling campaign results

Where to begin with the Namibia story. Since the 2024/2025 drilling campaign began last October, the market has reacted negatively to nearly every update, creating a perception of consistently disappointing news. Let me walk you through what's happened.

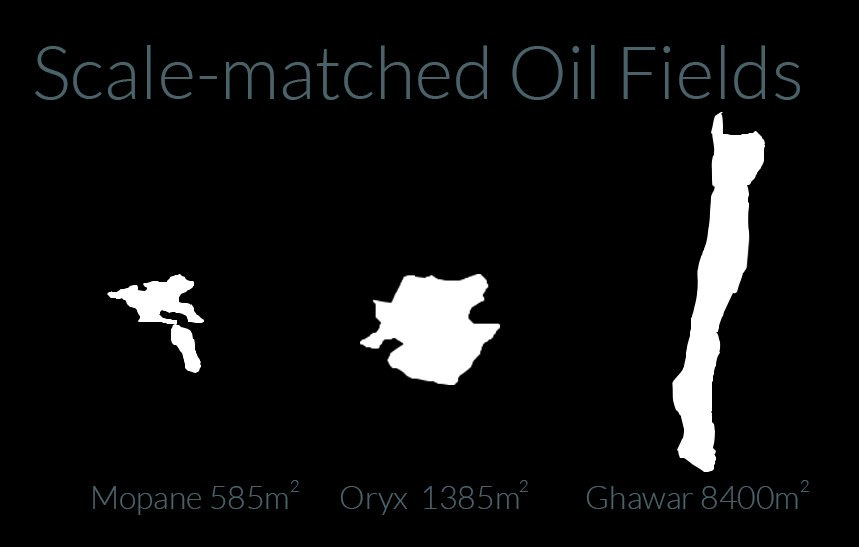

First up on the results front was Mopane-1A over in Block 2813A (PEL 83). Drilling at Mopane-1A began on October 23, 2024, and concluded by November 28, when the first results were released. They found some light oil and gas-condensate in what they called high-quality reservoir-bearing sands, but they were pretty tight-lipped about the details.

Then came Mopane-2A. The results came on the last day of the year, showing they found gas-condensate in AVO-3 but used words like "thin net pay" in the sweet spot. They also found some light oil in AVO-4, but again, they called it a "smaller" reservoir. The market wasn't thrilled with all these diminutive adjectives instead of actual numbers. In the same press release, Galp also announced a concurrent high-density and high-resolution proprietary 3D development seismic campaign over the Mopane complex. This survey will be crucial for both the next year’s campaign and a potential farm-out.

Kapana-1X in Block 2813B (PEL 90) results followed shortly after in January 2025. This one was a bit of a letdown - no commercial hydrocarbons, though they're putting a brave face on it, talking about "valuable information on the basin." I've seen some delusional takes on this one, including theories about Chevron deliberately drilling a risky prospect to squeeze Sintana (as you may know, Sintana was carried, from now on they must pay their part). The emphasis on 'valuable information' suggests two possibilities: either the discovery of a substantial but low-permeability reservoir (similar to the later commented Tamboti), or a non-commercial result that nonetheless provides important geological data. Regardless, further exploration is planned.

Then in February came the results from Tamboti-1X in Block 2913B (PEL 56), which they'd been drilling since October 2024. This one hit black oil in about 85 meters of Upper Cretaceous sandstones in the Mangetti fan system. Total's CEO was pretty blunt about it, basically saying "game over" because of low permeability. Interestingly, Impact Oil's press release offered a more optimistic perspective, emphasizing that analysis of the Drill Stem Test (DST) was ongoing. The general consensus is that, while a big pool of hydrocarbons were encountered, the find is not currently commercially viable (maybe a bit distant of Total’s required $20 per barrel cost), although it may contribute to a future, larger-scale Mangetti development.

We also can't ignore Shell's $400 million write-off on PEL 39, announced alongside these results. While the company cited technical and commercial challenges, the underlying issues reveal a complex interplay of geological factors that are complicating development across the region. The low permeability rock (Total mentioned Jonker permeability was a tiny 0.7mD and Venus 2-4mD) appears to be linked to chlorite cementation issues in the deep-water reservoirs.

Technical challenges

The presence of chlorite, an iron-rich clay mineral, creates an intriguing geological puzzle. Although this mineral is typically found in shallower marine environments, its unexpected presence in Namibian deep-water reservoirs indicates a more complex geological history than initially understood. This may involve volcanic rock fragments that provided the building blocks for chlorite formation during burial.

A moderate amount of chlorite can benefit reservoir quality by preventing quartz overgrowth during burial. However, excessive chlorite concentrations clog pore spaces, and its uneven distribution further complicates production scenarios. Compounding the issue, chlorite distribution is rarely uniform across reservoirs. This heterogeneity results in a patchwork of completely clogged sections interspersed with high-permeability streaks.

This reservoir heterogeneity creates particularly challenging production scenarios when combined with another critical issue: high gas-oil ratios. Due to the uneven permeability, gas preferentially flows through high-permeability streaks, potentially leaving oil trapped in lower-permeability zones. This challenge is especially acute in the Venus and Graff discoveries, which sit close to their source rocks, resulting in oil that's particularly rich in dissolved gas. As pressure drops during production, gas may preferentially flow through these high-permeability streaks into wellbores, potentially compromising oil recovery.

The gas management issue has become a major obstacle for development plans. Namibian law prohibits gas flaring, requiring operators to either reinject the gas or process it - a position supported by Petroleum Commissioner Shino as "the right thing to do."

TotalEnergies' CEO Patrick Pouyanné highlighted that reinjecting gas at depths exceeding 3,000 meters is inherently expensive, with required gas handling capacity potentially 500 million standard cubic feet per day instead of the initially anticipated 200-300 million. These additional infrastructure requirements are making it challenging for Total to achieve their internal requirement of capex plus production costs below $20 per barrel, necessary for a final investment decision (FID).

These reservoir difficulties distinguish Namibian developments from some other African successes. Consider Côte d'Ivoire's Baleine field: its lower gas-oil ratios allow for a simpler development approach, where operators can prioritize oil production before addressing gas management systems. Even more telling is the contrast with Guyana, where favorable reservoir characteristics enabled rapid development.

Still, these difficulties may not be uniform across the Orange Basin. Industry experts, such as Marcio Mello from BPS, suggest that reservoir quality may improve in blocks further north, beyond the Orange River's influence (e.g., Mopane and the Saturn Superfan). These compounding factors help explain both Shell's significant write-off and the broader delays in development decisions across the region, while also hinting at potentially better prospects in different parts of the basin.

It's worth noting that the recent Tamboti discovery targeted different stratigraphic horizons than Venus and Mopane, which are situated in the Albian-Aptian sandstone sequence. This geological distinction could be one of the reasons for its failure and may shed some hope over drilling again in the northern part of PEL 56 and PEL 90.

Despite these challenges, operators and authorities are working together on solutions. Galp has demonstrated the technical feasibility of gas reinjection as an initial operational approach. Building on this, the Namibian Ministry of Mines and Energy is taking a proactive role in coordinating basin-wide gas utilization strategies. Their initiatives include potential integration with the Kudu gas field development through gas-to-power projects or FLNG facilities, which could provide the necessary infrastructure for managing gas across multiple developments in the basin.

Ongoing operations and future prospects

Current drilling operations include Sagittarius-1X in Block 2914A (PEL 85), which commenced on December 18, 2024, with an estimated 45-day timeline. Market anticipation for this well is particularly high. Concurrent operations include Mopane-3X, which began on January 2, 2025, targeting two stacked prospects: AVO-10 and AVO-13.

Results from these wells are expected imminently. Hopefully something positive can be said and sentiment in the region improves a bit, as it seems everybody now thinks Namibia won’t produce oil. Total is still committed to making FID on Venus (now expected in 2026 instead of this year) with a 150k boe/d FPSO and shallower decline rates though it may also reflect ongoing negotiations over fiscal terms - IMO FID will happen this year and the FPSO will be a 160k boe/d, probably Hanwha Ocean.

The drilling campaign continues to expand. Marula-1X began on February 3, 2025, in Block 2913B (PEL 56), targeting Albian-aged sandstones in the Marula fan complex, potentially opening new possibilities in the southern Kudu source-rock kitchen. The well is targeting 2 billion barrels, making it larger than Tamboti. Later in 2025, Olympe-1X (Block 2912, PEL 56) will utilize the Deepsea Mira to explore Albian sands in a structural closure. BW Energy's Kharas-1X (PPL 003) is scheduled for the second half of 2025, with the company pursuing rig-sharing arrangements, likely with Galp or Total, to optimize costs.

While recent results have disappointed market expectations, this reaction should be viewed within the context of typical exploration cycles. The pattern closely mirrors the Lassonde curve in mining, which describes the evolution through Discovery, Exploration, Engineering, Development, and Production phases. The offshore oil and gas sector typically experiences even more pronounced volatility due to its capital-intensive nature, with single wells often costing up to $100 million.

This context helps explain the current market phase. Not only is the discovery important, but its commerciality is also crucial. After results from Sagittarius, Mopane-3X, and Marula, activity will likely enter a quieter period until the second half of 2025. Key catalysts during this period could include Galp's potential farm-out and Woodside's farm-in completion, with the latter's commitment to drilling the sizeable Oryx prospect being particularly significant.

While market sentiment appears driven by recent drilling results, the Orange Basin's exploration history offers valuable context about the evolution of geological understanding and the importance of persistence in frontier basins. Check out our previous article:

Field notes: Introduction to Namibia

As for myself, most Sintana Energy’s shareholders aren’t geologists and, sometimes, reading about the different basins located offshore Namibia can be confusing. This post aims to give some context on several pieces of information regarding the relevance of the discoveries in Namibia and why the Campos and Pelotas Basins could be good peers to compare w…

But in short, in 2010, Brazilian company HRT, led by geologist Marcio Mello (who had played a key role in discovering Brazil's pre-salt play), ventured into these waters. Their Moosehead-1 well, drilled almost on trend with today's Mopane, could have opened up the Orange Basin years earlier. They were targeting Barremian-aged carbonate reservoirs, hoping to find equivalents to Brazil and Angola's pre-salt reservoirs. While they found about 100 meters of carbonates at their primary target, the reservoir wasn't developed as expected.

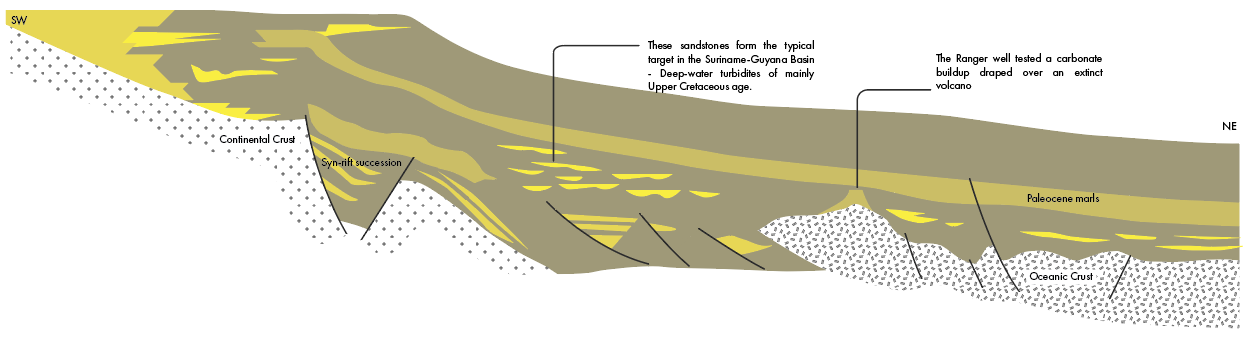

The most significant discoveries would ultimately be made in deeper waters, within sediments overlying oceanic crust - a play concept that remained unproven until TotalEnergies and Shell's 2022 discoveries, twelve years after HRT's campaign. Even more interesting is that the shift from targeting pre-salt analogues to deep-water plays wasn't TotalEnergies' original insight.

It was the late Dave Roads from Impact Oil and Gas who interpreted the Venus prospect, drawing inspiration from Ghana's Jubilee field to focus on Cretaceous systems rather than Tertiary targets. At the time, as Phil Birch, who has just left Impact, noted in London in 2022, the biggest risk in mapping Venus was the charge model - many thought it impossible to cook a source rock overlying oceanic crust. That model has been thoroughly revised.

This historical context underscores a fundamental truth about exploration, particularly in frontier areas: risk is inherent, and success often follows multiple iterations of learning. The industry has seen this pattern play out repeatedly in major basins around the world. The evolution of Guyana from a frontier basin to a world-class oil province offers particularly relevant insights for understanding Namibia's potential trajectory. Both regions share notable parallels: early technical setbacks, the necessity for persistent exploration, and successful challenges to conventional wisdom about deepwater plays. Examining Guyana's development over the past decade provides a valuable framework for assessing Namibia's current position in its exploration journey.

Guyana: Initial offshore exploration

Guyana's oil and gas exploration story can be traced back to the 1750s when Dutch explorers discovered flotsam pitch, indicating the presence of hydrocarbons in the region. Further evidence emerged in 1917 with the observation of small pitch deposits near Krunkenal Point. These early findings sparked interest in Guyana's petroleum potential, leading to the first oil prospecting license being issued to Trinidad Leaseholds Company Ltd in 1938.

Onshore exploration continued throughout the early 20th century, with a well drilled at Plantation Bath in 1926 providing enough gas to be used at the local sugar factory. However, most onshore prospects proved unsuccessful. In 1965, offshore licences were granted to Conoco and Shell, and nine wells were drilled between 1965 and 1970. Of these, only the Abary-1 well in the Kanuku license area struck oil (API of around 37°). While these early efforts did not yield commercially viable discoveries, they confirmed the presence of a functioning petroleum system, setting the stage for future exploration activities.

In the early days of offshore exploration, Guyana resembled a wild frontier where operators had little choice but to learn by drilling—and by drilling dry. Before the game-changing breakthroughs of the 2010s, early operators were testing the waters with limited seismic data and outdated drilling technology. Much like Namibia's own early forays, when Chevron first struck the Kudu gas field in 1974, Guyana's initial attempts were as much about gathering geological intelligence as about finding commercial quantities of hydrocarbons.

In the 1980s, the Government of Guyana actively promoted and attracted investors for exploration in the country's emerging petroleum industry. This initiative was supported by the World Bank, which provided financial and technical assistance. The Guyana Geology and Mines Commission (GGMC) played a crucial role in recording and documenting these exploration activities.

Despite renewed efforts, exploration in the 1980s and 1990s faced challenges. Companies struggled to raise funds for offshore drilling programs, and a maritime boundary dispute with Suriname further hindered progress. In the mid-2000s, CGX Energy's attempt to spud a well (Eagle Prospect) was halted by Surinamese gunboats, underscoring the need for clear maritime boundaries. This issue was eventually resolved in 2007 by the United Nations International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS), paving the way for future exploration.

What's key to understand is that these initial "failures" and sub-commercial tests were not missteps but integral steps in the journey toward major discoveries. In both Guyana and Namibia, the early wells helped build the geological models that later guided more sophisticated exploration programs. Every dry hole or marginal flow was a piece of the puzzle—an essential part of reducing risk and refining future targets. These pioneering efforts set the stage for the dramatic breakthroughs of the modern era, proving that exploration is as much an art of learning from the misses as it is a science of celebrating the hits.

The Modern Era: The Liza Breakthrough and beyond

The modern era of offshore exploration in Guyana represents a remarkable transformation, where uncertain early tests evolved into a sophisticated, technology-driven campaign that would fundamentally reshape our understanding of deepwater prospects. The advent of advanced 3D seismic imaging technology played a pivotal role in this evolution, allowing operators to visualize subsurface structures with unprecedented clarity. These technological advances enabled geologists to identify subtle stratigraphic traps and complex reservoir architectures that had previously gone unnoticed, setting the stage for a series of breakthrough discoveries.

The watershed moment came in 2015 when ExxonMobil announced a discovery that would change the trajectory of Guyana's petroleum history. The Liza-1 well, drilled approximately 200 kilometers offshore to a depth of 5,433 meters, encountered more than 90 meters of high-quality, oil-bearing sandstone reservoirs. The choice of the Liza structure as the initial target wasn't arbitrary - advanced seismic processing had revealed a promising combination of structural closure and high-amplitude anomalies, suggesting the presence of hydrocarbons trapped in high-quality reservoir rocks.

The success of Liza-1 catalyzed an aggressive exploration and appraisal campaign to assess the full extent of this new play. Liza Deep (Liza-3) tested the vertical reach of the reservoir system, revealing additional pay zones beneath the original discovery and highlighting the vertical stacking that would become a hallmark of Guyana’s petroleum system. Building on this momentum, Payara-1 targeted a geologically related structure, confirming the petroleum system extended beyond Liza and demonstrating consistent reservoir quality—porosity and permeability values matched or exceeded those at Liza—suggesting a regional-scale depositional system capable of producing extensive, high-quality reservoir units.

The pace and success of these early discoveries were unprecedented in modern exploration history. Within just two years, operators had progressed from an initial discovery to a comprehensive understanding of a major new petroleum province. Each well brought new insights into reservoir distribution, fluid properties, and production characteristics, rapidly de-risking the basin and setting the stage for what would become one of the industry's most successful exploration campaigns.

As the exploration campaign gained steam, each discovery transformed initial success into a world-class opportunity. Pacora-1 and Longtail-1, both drilled in 2018, reinforced the basin’s exceptional potential: Pacora-1 encountered around 20 meters of high-quality sandstone, while Longtail-1 revealed an impressive 78-meter pay zone. Together, these wells added substantial volumes to the resource base and refined understanding of reservoir connectivity.

Hammerhead-1 and Pluma-1 further delineated complex reservoir geometries, providing crucial data for optimizing production well placement and building more sophisticated reservoir models. These advances led to remarkable growth in estimated recoverable resources—eventually surpassing 11 billion barrels of oil equivalent—an outcome that would have seemed improbable during Guyana’s frontier exploration phase.

However, the path to success wasn't without its challenges, and these setbacks proved just as instructive as the victories. The Skipjack-1 well, drilled in 2016 amid the early optimism following the Liza discovery, served as a sobering reminder of exploration risk when it failed to find commercial quantities of oil. Beyond the prolific Stabroek Block, the Tanager-1 well in the Kaieteur Block encountered hydrocarbons but proved non-commercial as a standalone development. In the Canje Block, the Bulletwood-1 well returned as a dry hole despite its promising pre-drill potential. These results highlighted the complexity of replicating Stabroek's success in adjacent areas and emphasized the importance of understanding subtle variations in geological conditions across the basin.

The Kanuku License area presented its own unique learning opportunities. The Beebei-Potaro well found well-developed reservoirs but they were water-bearing, while Carapa-1 discovered low-sulfur oil in poorly developed reservoirs. The Uaru-2 well showed promising hydrocarbon indicators but faced complex reservoir characteristics that required additional evaluation. Each of these "disappointments" contributed valuable data points to the broader exploration effort, helping operators refine their geological models and better predict reservoir quality distribution across the basin.

What makes Guyana's story particularly remarkable is how these setbacks were transformed into stepping stones for future success. ExxonMobil's impressive success rate of 80% - it is said to reach even 90% - wasn't achieved by avoiding risk, but rather through systematically learning from each well, whether successful or not. The unsuccessful wells often provided crucial insights about reservoir distribution, migration pathways, and trap integrity that proved invaluable for subsequent exploration efforts. This systematic approach to learning and adaptation offers valuable lessons for other frontier basins, where success often depends on maintaining momentum through inevitable setbacks while continuously refining geological understanding.

What’s next?

The Orange Basin story is still unfolding, and we have yet to pinpoint which block might emerge as Namibia’s equivalent of Guyana’s prolific Stabroek. While Venus and Mopane remain strong contenders, the basin’s ultimate potential could lie in areas that are only beginning to be explored. In spite of recent negative sentiment, the fact that industry heavyweights continue to increase their stakes in the region is telling: for instance, Total boosted its ownership in Blocks 2913B and 2912 last year, and QatarEnergy farmed in to Chevron’s PEL 90 during the Kapana-1X well drilling. These moves underscore that major operators with deep insights into local geology still see substantial opportunity.

Major investments of this kind reinforce the view that Orange Basin–focused equities, such as Sintana Energy, Africa Oil and Pancontinental Energy, may be fundamentally undervalued. Even with skepticism surrounding the region, development of Venus appears inevitable—Total intends to reach first oil in roughly four years, an accelerated schedule for a large offshore project. The time frame alone highlights the basin’s attractiveness and the operators’ commitment.

Mopane’s potential similarly appears underestimated. Despite evolving market sentiment, the field’s geological fundamentals have not changed significantly. Concerns around chlorite cementation, high gas-oil ratios, and limited permeability—while clearly impacting parts of the basin—may be less relevant here. If and when Galp resumes its wider campaign across the Mopane block, discussions are likely to pivot back to the substantial oil-in-place figures that first attracted industry interest.

Looking ahead, the Saturn Superfan prospect in 2026 could prove transformative if it yields results that surpass existing discoveries. The hasty dismissal of entire licenses—such as writing off PEL 90 following a single Kapana-1X well—overlooks the inherent learning curve in frontier exploration. Simply put, one underwhelming result does not define the geological potential of an entire block.

As operators refine drilling targets and continue to de-risk the play, capital decisions become paramount. Sintana’s management faces a pivotal choice between further farmdowns and raising additional equity. Given their track record, they will likely seek a route that preserves shareholder value, balancing near-term financing needs with long-term basin potential.

Another overlooked catalyst is BW Energy’s upcoming drilling campaign, which has drawn limited market attention despite being integral to regional economics. A discovery at Kharas could accelerate projects in multiple blocks by leveraging shared gas or infrastructure solutions, helping de-risk development costs and timelines across the basin.

Ultimately, the difference between current valuations and the basin’s underlying fundamentals suggests an opportunity for patient investors who recognize that frontier oil and gas development rarely proceeds smoothly. As technical solutions to reservoir and gas-handling challenges mature—and as operators converge on robust development plans—today’s skeptical sentiment may give way to a reassessment of the Orange Basin’s true long-term value.

The views expressed herein are personal opinions and do not constitute financial or investment advice. All investing carries risk, including potential loss of principal. Readers should conduct their own research or consult a licensed financial professional before making any investment decisions. The author may hold positions in some of the securities mentioned.

As a specialist in drilling, this is impressive insights !

Great write up guys, thanks 🙏