Seplat Energy's acquisition of Mobil Producing Nigeria Unlimited (MPNU) represents a transformative but high-risk transaction:

Financial Impact: Assets show negative post-tax NPV under current terms, with 85% tax burden severely limiting cash flow generation.

Growth vs. Risk: While the deal doubles production and reserves, it requires substantial capital investment ($475M peak in 2027) with uncertain returns.

Key Challenge: Success depends heavily on transitioning to more favorable tax terms under Nigeria's Petroleum Industry Act - without this shift, the investment thesis becomes difficult to justify.

The transaction positions Seplat as Nigeria's leading independent E&P player but at a potentially unsustainable financial cost under current fiscal terms.

Initial Deal Promise vs. Reality

Seplat today published the long-awaited Prospectus for MPNU acquisition. The proposed acquisition, which began over two years ago, was heralded as a transformative opportunity. Investors envisioned Seplat doubling its production, bolstering reserves, and solidifying its status as a leading indigenous energy company in Nigeria. The narrative seemed perfect: years of ExxonMobil's underinvestment provided a chance for Seplat to restore productivity and unlock significant value. Optimism surged, buoyed by mechanisms like the lockbox structure and the potential shift to more favorable tax regimes.

Yet, as always, the devil lay in the details, and the picture doesn't look pretty. While the headline numbers appear incredible - showing triple-digit growth in volumes and reserves - the economic reality of the deal (which we have attempted to assess over time) falls far short of expectations.

After a flurry of approvals from regulators, ministries, and the Nigerian president, the deal appeared poised to close by year-end. While our timing prediction proved accurate, our broader expectations did not materialize.

In my earlier commentary, I maintained an optimistic outlook. The acquisition structure, underpinned by the lockbox mechanism and the opportunity to capitalize on years of underinvestment by Exxon, appeared to be a masterstroke. Under the PIA, the deal could be not only self-funded at closing, but Seplat could even receive cash (despite an undisclosed Profit Sharing Scheme).

However, markets hate uncertainty. Following a review of the fiscal terms prompted by Mr. Brown's video commentary, I exited my position, as noted in my X account, preferring clarity over speculation. My revised model suggested that while the deal wasn't quite as compelling under the Petroleum Profits Tax regime (PPT), it still presented upside but I was not comfortable with the uncertainties. In hindsight, the final terms seem even worse than my revised model, reinforcing my decision to sell.

The deal's closing now feels like a double-edged sword: while Seplat has undeniably secured its place as Nigeria's leading independent E&P player, the less favorable terms and financial strain leave little room for missteps. This article examines how the deal evolved, why optimism waned, and what the final terms mean for Seplat's future.

The Financial Reality

The final consideration structure reveals the complex nature of this transaction. The headline price of $800 million ($128 million already paid as deposit, $672 million due at closing) is just the beginning. Not only was the deal not self-funded as many wished, but it adds significant leverage to Seplat.

There's an additional $257.5 million deferred to December 2025 for decommissioning, abandonment, and JV costs, though the net after-tax impact on MPNU is expected to be more modest at $25-35 million. The deal also includes contingent payments of up to $300 million over five years (2022-2026), of which $43 million is already due for 2022-2023. Apart from this, the analysis of MPNU's financial structure reveals a concerning picture dominated by two critical issues: an overwhelming tax burden and challenging capital expenditure requirements that threaten future free cash flow generation.

The Crushing Tax Burden

The most striking revelation from the prospectus is the crushing tax burden these assets operate under. While the Petroleum Profits Tax (PPT) rate of 85% might not be unexpected in isolation, its practical impact on cash flows has proven more severe than anticipated. Historical analysis demonstrates the magnitude of this burden: in the past three years, taxes consumed 81%, 87%, and 88% of operating cash flow, leaving minimal resources for growth initiatives or shareholder returns. How did ExxonMobil allow this to happen? The main winner here is the Nigerian government:

This tax regime's impact becomes even more apparent when examining Net Present Value (NPV) calculations. Despite showing significant pre-tax potential with 2P NPVs of $7.2 billion at a 0% discount rate, the assets' post-tax NPVs turn deeply negative at most reasonable discount rates. Even with a relatively generous 10% discount rate for Nigeria's challenging jurisdiction, the post-tax NPV ranges from negative $836 million to positive $2 billion, depending on reserve categorization. This stark reality helps explain ExxonMobil's strategic withdrawal and raises fundamental questions about the acquisition's value proposition under current terms.

Capital Expenditure Requirements, Production Outlook and Challenges

After the final consideration to be paid to Exxon, the second thing we looked at was the ability of MPNU to generate FCF in the last few years. Well, the answer was surprising for the worse. As expected, MPNU’s CAPEX since the deal was announced was reduced to the bare minimum, which confirms that ExxonMobil was certain that it didn’t want to continue operating the licences included in MPNU.

Here is also the Cost of Sales.

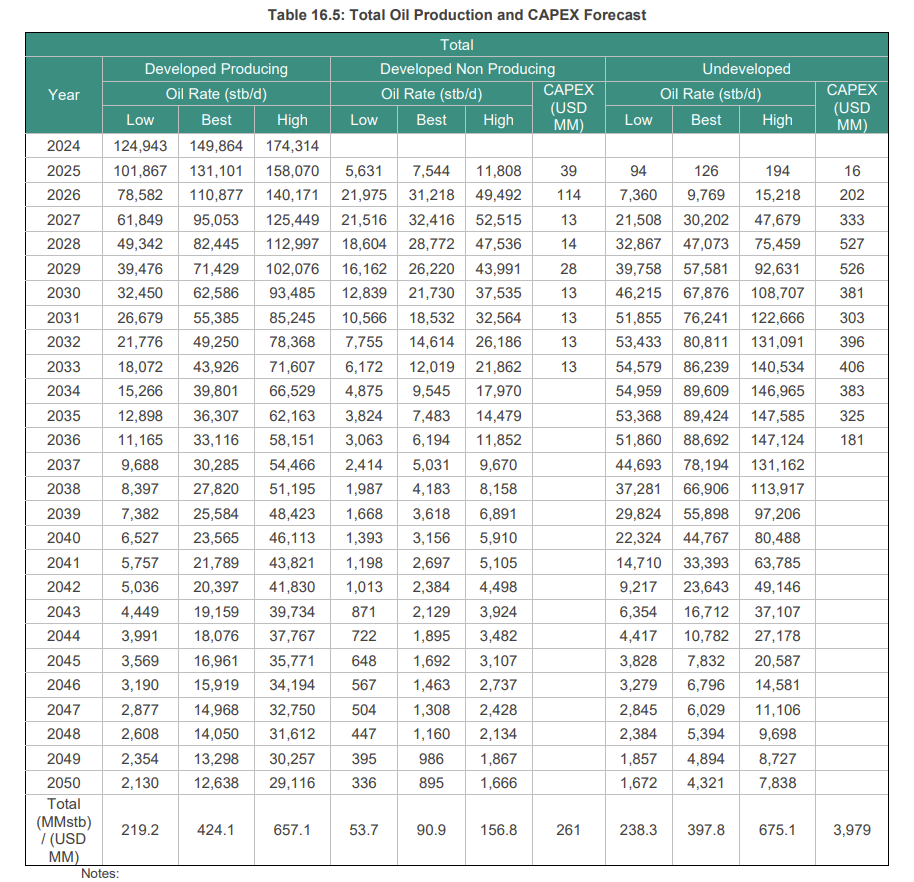

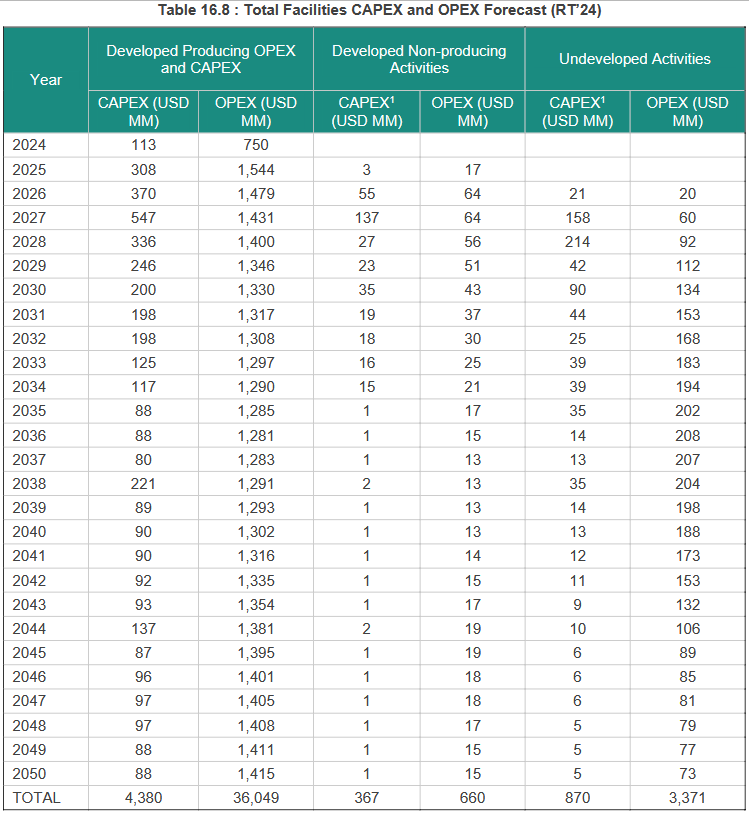

The prospectus includes some forecasts for the expected production, CAPEX and OPEX, and they are more bitter than sweet. As expected, the CAPEX in the next few years has to make up for the lower investment level since the deal was first signed. This will increase the group’s CAPEX to unseen figures.

To add some context, this year’s CAPEX is expected to be around $200 million and the investment in production growth required by OMLs 67, 68, 70 and 104 alone will be $312 ($125 net) million in 2025, growing to $595 ($238 net) million in 2027. Despite this being huge numbers, it's not the only CAPEX required by these OMLs.

Hence, Seplat will need to optimize its cash generation capacity in the coming years, a task that appears challenging based on the recently disclosed post-tax cash flow from operations (CFFO) figures.

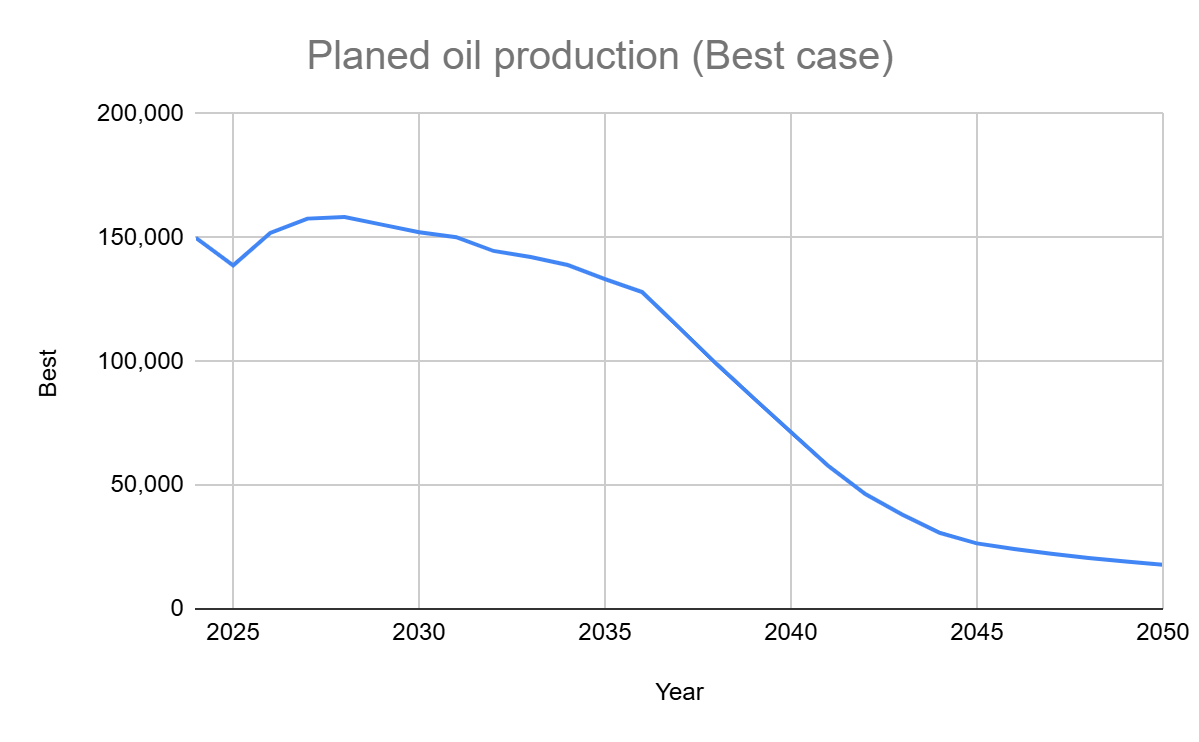

The gross oil production in the following years will be more or less flat even after the projected insane levels of CAPEX. The future production curve is the following:

One may think that this heightened CAPEX would substantially increase the production of the fields, but there is a series of commitments that are not related to production growth or decline compensation. For example, these 2 items alone will result in a net expenditure of $56 million per year without resulting in additional barrels.

$575 million over seven years (2026-2032) for platform structural repairs which covers repair of 23 platforms

$411 million over seven years (2027-2034) for pipeline replacement programme

See 13.3. Capital Expenses of the Prospectus (gross figures)

With the total CAPEX for facilities (on top of the production CAPEX) reaching staggering figures as high as $842 ($337 net) million in 2027.

Seplat will experience a monstrous net CAPEX of $475 million, $447.2 million and $346 million in 2027-2029. How would Seplat’s stake in MPNU cover these investments without requiring external funds?

There is additional upside in the NGL and natural gas production, plus the midstream assets of the group, but oil production will still become the largest contributor to the top line of Seplat’s financials. Even with more benign fiscal terms, the natural gas and midstream segment cannot compensate for the situation for the oil production.

Thus, the company will barely generate any FCF from these assets in the following years. So, it is highly likely that the company needs additional cash from the existing businesses to maintain this high level of investment. This has already been recognised in the risks section:

The prospectus gives a grim outlook of high CAPEX levels, sustained oil production rate and additional financial resources to finance these plans. It is not the idea we had when we first approached this deal and we believed in the potential of OMLs 67, 68, 70 and 104. We anticipated a large CAPEX increase the years after the deal was closed, but we didn't foresee the very low FCF yield and enormous CAPEX for facilities. In view of these facts, the deal is a hard to swallow pill for shareholders. We thought it was a steal for Seplat, now we see Exxon made the better deal.

Implications for Seplat's Future

In summary, the prospectus is clear and leaves no room for interpretation: the MPNU assets have a negative post-tax NPV under the current fiscal framework. This alone makes the transaction a risky gamble, hinging on the Nigerian government's willingness to transition these assets to the more favorable Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) tax regime.

For those who may consider the potential upside, this deal isn’t about the present or even immediate future value of these licenses—it’s about a bet on fiscal reform. If, and only if, the government approves the transition to PIA, these assets will become profitable, generating enough cash flow to justify the acquisition cost. Until then, they remain a liability, with high costs and limited returns.

At present, the ‘old’ Seplat—with its existing portfolio and the upcoming ANOH plant—is more profitable than the enlarged ‘new’ Seplat.

The decision to ramp up production without securing PIA terms first risks significant value destruction. While management may believe this signals commitment to the government and strengthens their case for reform, it’s a gamble that assumes the government will act rationally and prioritize long-term oil and gas production over immediate fiscal needs. Unfortunately, as the deal’s two-and-a-half-year delay demonstrates, there’s little evidence to support such optimism.

Investing in Seplat at this juncture is, therefore, a speculative bet on three key developments:

Ramping up production: Seplat must reverse years of underinvestment in MPNU assets to restore meaningful production growth to pre-COVID levels. The company needs to achieve a production growth that exceeds the forecasts outlined in the Prospectus.

Transition to PIA: Without a transition to the PIA fiscal framework, even improved production won't salvage the negative NPV of these assets. The lack of certainty is evident in statements such as ERCE's disclosure: "Seplat Energy Offshore Ltd (SEOL) has informed ERCE that the expectation is that at some stage the assets will be under the terms of the PIA. It is currently unclear when this would happen." Such ambiguity does little to inspire confidence.

The 2026/27 story: Only in the medium term, contingent on both successful fiscal reform and production ramp-up, could the cash flow profile of the MPNU assets justify their acquisition price.

This acquisition must be viewed within the broader context of International Oil Companies (IOCs) retreating from Nigeria. Recent high-profile divestments—Equinor's $1.2 billion exit and TotalEnergies' $860 million departure—paint a clear picture: major players are voting with their feet. While security concerns, theft, and regulatory uncertainty are often cited as driving factors, the fundamental issue is simpler: the economics no longer make sense. Operating under an 85% tax burden in a mature basin is difficult to justify when more attractive opportunities exist elsewhere globally.

The pattern is telling: while Nigerian officials speak of attracting foreign investment, their reluctance to transition these assets to the more balanced PIA tax regime undermines such rhetoric. Indigenous firms like Seplat and Chappal Energies are stepping into the void left by departing IOCs. While this might appear to present opportunities to acquire assets at attractive valuations, these local players inherit the same structural challenges that drove their international counterparts away. Without meaningful tax reforms or regulatory improvements, the apparent advantages of these acquisitions could quickly evaporate.

Even under these optimistic scenarios, the risks remain substantial. Nigeria is a challenging jurisdiction with high discount rates—15% is conservative, and 20% might still be too low for a realistic risk-adjusted valuation. Even considering 3P reserves (proven, probable, and possible), the numbers barely provide a margin of safety for investors.

Ultimately, this deal reflects management’s belief in the long-term story. However, for the average investor, it’s a difficult proposition. Most would rightly avoid risking capital on the assumption that the Nigerian government will act decisively to support reform. The more prudent strategy is to stay on the sidelines and wait for clear signs of progress—whether that’s fiscal reform, successful production ramp-up, or significant improvements in cash flow generation.

As it stands, Seplat faces a tough road ahead. Without fiscal transition, the risks outweigh the rewards, and significant value destruction is a real possibility. Investors should remain cautious and approach this story with skepticism until the company secures better—and fairer—fiscal terms.

Disclaimer: This post includes the first impressions after reading the prospectus released today. A final analysis will be completed in the next few days and our conclusions may change for the worse or the better. We will not publish a follow-up unless we see a significant divergence from the views shared here. We may publish some additional thoughts on Twitter/X, follow us there if you are interested. This text is not a recommendation in any way; it's just the opinions of its authors.

That's why we also looked at the capex required the next years. More capex may lower the tax bill, but Seplat will have to pay those record levels of CAPEX. The situation may progressively improve after 2027, but without a significative increase in production, it's impact will not last long. The PIA regime is critical here.

The last three tax years will have little to no expenditure on drilling or other operations that can contribute to lessoning the tax burden so focussing your assessment on these is misleading.